The Three Lives of Josephine Baker - Part One: Freda

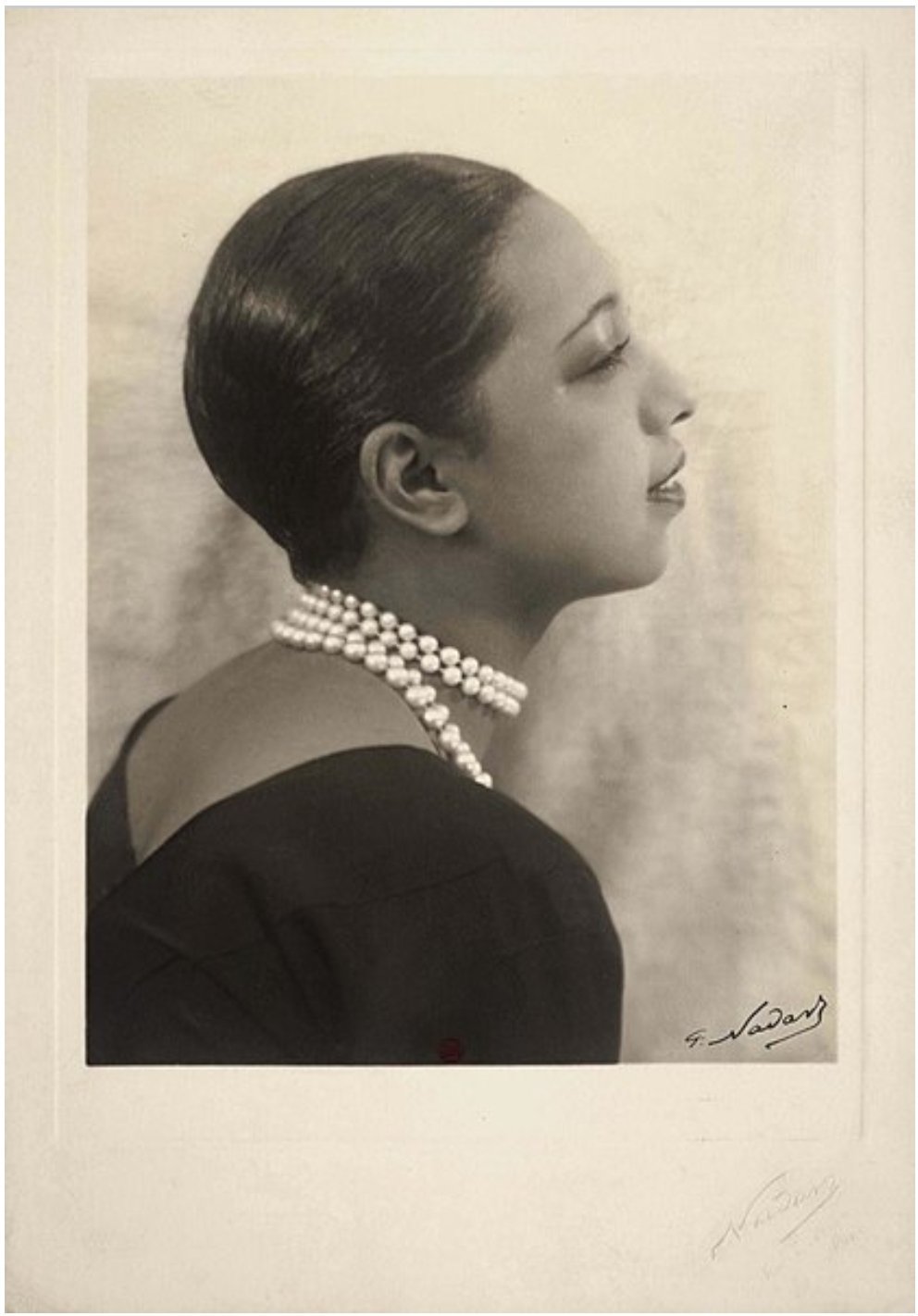

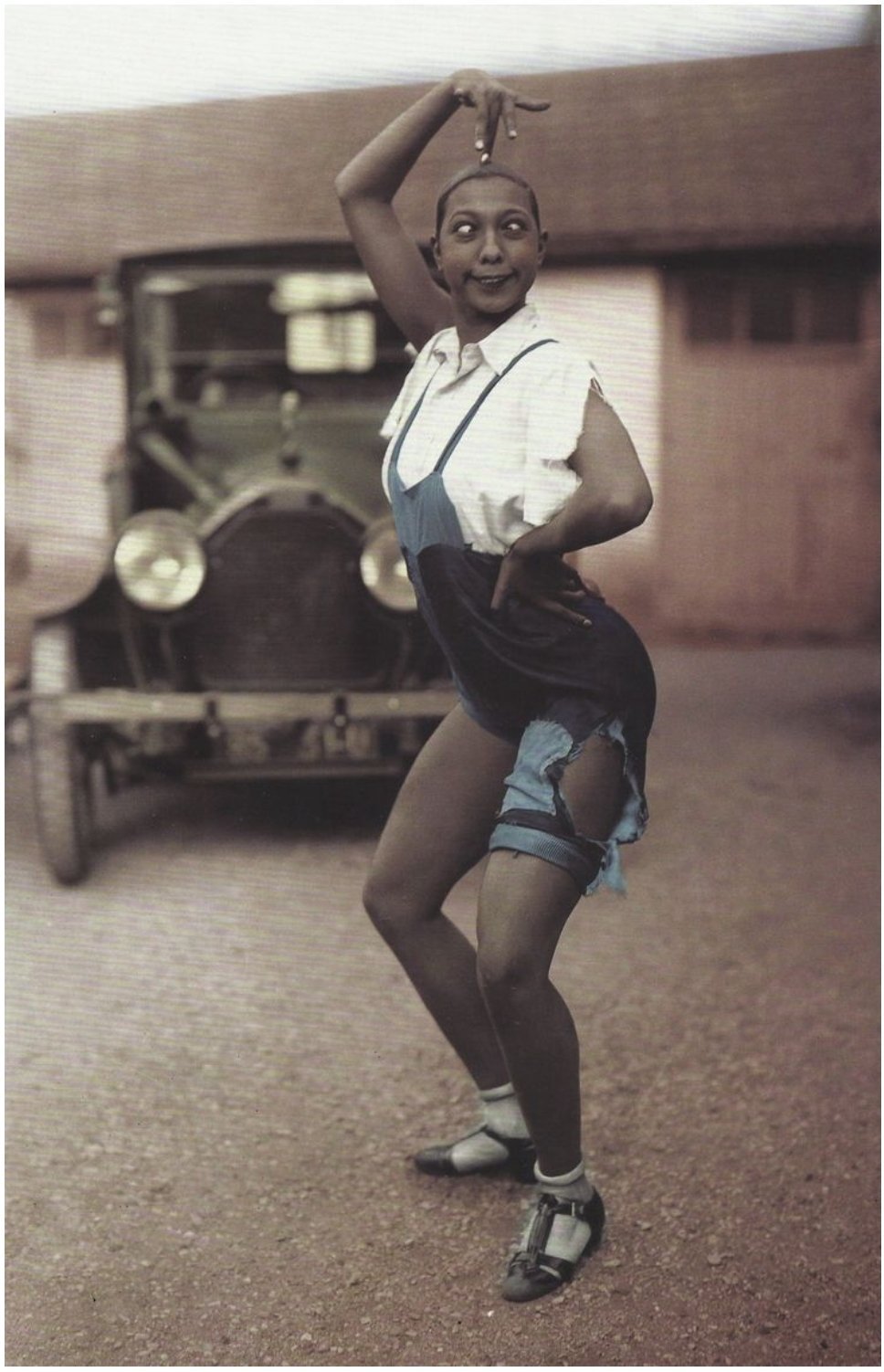

Early headshot of then Freda Josephine McDonald before Josephine became her stage and personal name. Date unknown. (Photo Credit: Pintrest)

Paris was instantly known globally as the ‘City of Light’ after becoming the second European metropolitan behind London to shine at night by way of the gaslight street lamps in the 1820s. Luminescence defines the Paris of today from the brightened corridors of terraces showing off its impressive catalog spanning the Gothic and Renaissance architectural eras to the bustling 'rues' leading drivers to circle the lit Arc de Triomphe and paths escorting millions to The Eiffel Tower which sparkles after dusk and well past nightfall. Each represents the many symbols associated with this beaming nexus of French culture and couture. However, it took nearly 100 years after the city first experienced the thrill of constant light to gain its most celebrated beacon hailing from the United States in the 1920s. The one, the only, Josephine Baker.

Photograph of Freda at the age of two from 1908. (Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

Born Freda Josephine McDonald along the muddied banks of The Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri on June 3, 1906, the infant who would in time become Josephine Baker arrived at 212 Targee Street in the low-income, mixed-race neighborhood close by to Union Station. The area juxtaposed the glitzy estates she would call home in the future as she walked the streets lined with rooming homes and brothels with women advertising their bedroom skills to passing clientele. Needless to say that Freda’s awareness and maneuverability in the streets became second nature at a very young age. Carrie, her mother who herself was adopted by former slaves Richard and Elvira McDonald in 1886, brought young Freda up as a single parent while making a living as a domestic worker taking in laundry for prominent white families in St. Louis. Many biographers of Josephine Baker conclude that her father was Eddie Carson who was a touring vaudevillian drummer while others claimed that her ‘real father was a white man’.

Then only eight years old, Freda soon joined her mother as they worked to produce more income to suffice for the lack of funds her new stepfather, Alan Martin, had difficulty providing with frequent patches of unemployment. Working with her mother provided the financial gains needed to survive and provide for Freda and her three new stepsiblings, but also painfully introduced her to the unwarranted privilege whites had, and still do, to levy unwarranted abuse. Her employer ran scalding hot water over her hands when she accidentally used too much laundry soap in the wash. It was worse off the clock, too. On the night of July 3, 1917, when she was eleven, Freda’s young eyes witnessed from across The Mississippi River the fiery razing of East St. Louis, Illinois as the bloody East St. Louis Race Riots commenced. Whites stormed black neighborhoods in droves leaving over 100 ‘negroes’ dead after the smoke cleared and dawn spotlit the destruction on that Fourth of July morning.

Image of the front page of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat from July 3, 1917, detailing the East St. Louis Race Riots that left 100 blacks ‘shot, burned and clubbed to death’ which a young Freda witnessed as an adolescent. (Photo Credit: SFBayView.com)

The country young Freda inherited was scorching with racism and blaring with indifference to the mere existence of black people beyond endless grinning servitude and countless forms of demeaning humor. These societal norms, set in place long before Freda was born, would stain her view of The American Dream that many people of color were told to reach out and grasp but rarely touched. Three years removed from that riotous summer night, the improvisational art of expression alive in jazz would begin musically keeping time with the crazed heyday of The Roaring Twenties for the entire nation. It proved to be the undeniable force of sound in color that also orchestrated Freda into the woman she would soon become for the entire world to see.

The dizzying, whirlwind pace of The Jazz Age’s start was the same way things moved for Freda. After dropping out of school at twelve and becoming a street dancer and a waitress at Pine Street’s Old Chauffeur's Club at the unbelievable age of thirteen, she was married–divorced–and then married again all before her sixteenth birthday and was a member of the touring vaudeville troupe named The Dixie Steppers. Blatant colorism by the group led to it initially rejecting her for being ‘too dark’ along with her being considered to be ‘too skinny’. The second man to place a ring on her adolescent finger was William Howard Baker whose surname she dedicated to keeping even after their divorce was finalized four years later in 1925.

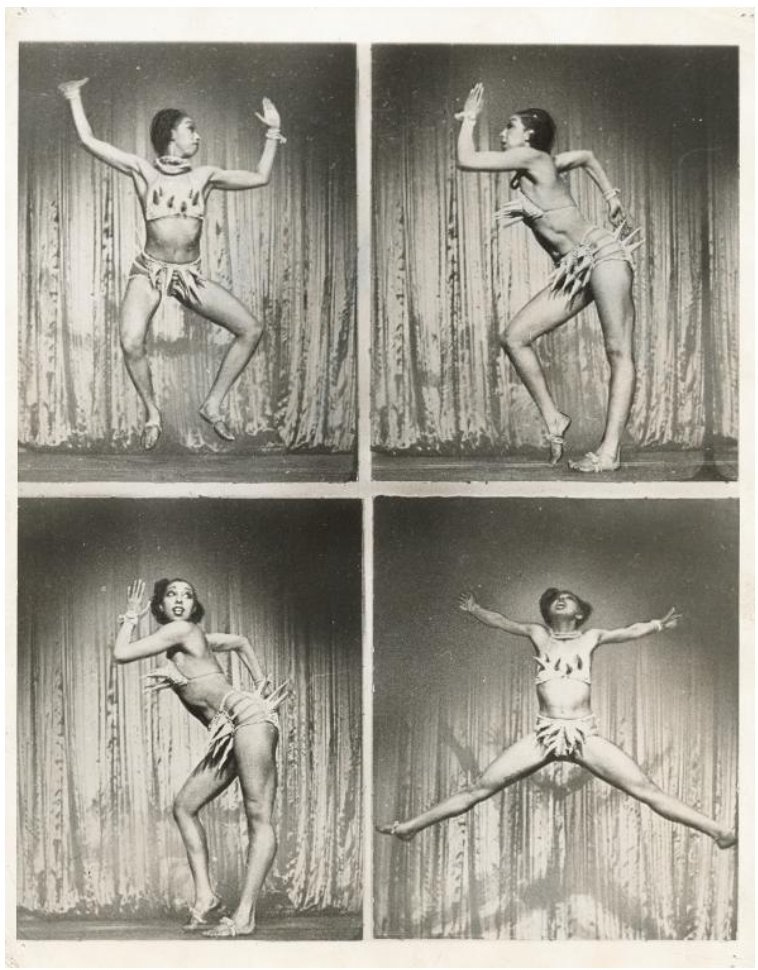

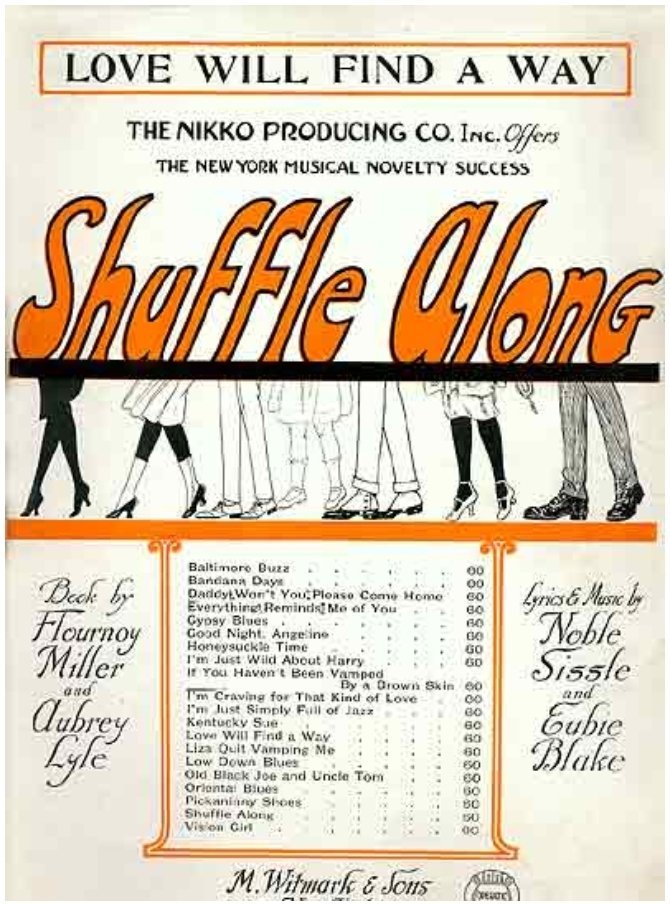

Her roles as a teen bride failed to stand the test of time, but her increasing love to entertain on street corners with song and dance was independently growing despite her mother’s disapproval that heightened the growing rift between them. She continued with The Dixie Steppers during her two marriages, but never got the opportunity to do more than just bit parts in comedy skits as a funny-faced dancer at the end of the chorus line. Freda began performing with the Jones Family Band when The Dixie Steppers stopped touring and was able to broaden her abilities past the low standards that was initially asked of her on stage. This led to her big (and final) break in the United States when her new troupe traveled to New York City to perform in the musical ‘Shuffle Along’ on Broadway at the peak of The Harlem Renaissance. Various performances followed where she danced on many stages around 125th Street and at The Plantation Club. In 1924, she landed another part as a chorus girl in the musical ‘The Chocolate Dandies’ written by the legendary team of Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle.

Eyes widened from just a taste of stardom, Freda’s aspirations expanded past any notion of ever returning to the St. Louis she remembered from her very recent youth. Her appetite for more stage time in a new city was whet. She was no longer using her first name and made the choice to go by her middle name–Josephine. There was no turning back to St. Louis to live the life her mother and America wanted for her. Paris was the destination she yearned to reach for and grab hold of when she sailed away in 1925 as a part of the all-black touring ensemble of dancers and musicians called ‘La Revue Negre’ (The Black Review) after being noticed by a French talent scout.

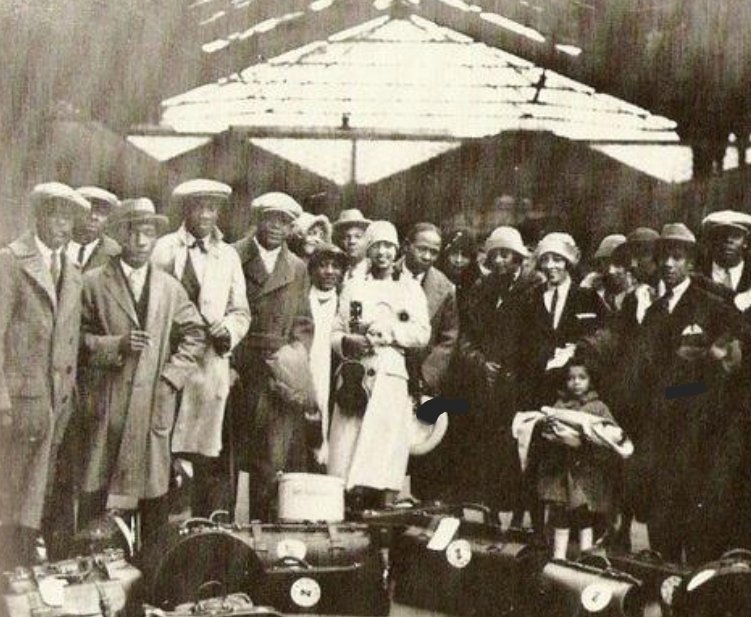

The cast of ‘La Revue Negre’ with Josephine Baker standing in the center before departing for Paris in 1925. (Photo Credit: Twitter)

"Josephine Baker, at that moment, was a very frightened girl," Baker said of herself in a 1960s televised interview with the British Broadcast Corporation in her later years. "Yes, frightened because–you see–there were special reasons for that fright and uncertainty. Josephine Baker was the girl who left St. Louis to come to Europe to find freedom."

There were no chains physically holding the rising stage star, but she could feel the restraint many black people of her time felt then locking them into limiting destinies not aligned with their boundless dreams. Josephine was no longer fused to the life prescribed for Freda. Josephine's decision to follow the vibe of creativity that guided her to embark on this courageous voyage was the abolishment of what America had shown her since birth. Her trek across the Atlantic Ocean to Paris would in time prove to widen her scope of opportunity abroad as well as start the new age for black travel soon opening our minds to new realities abroad.

Check in next Wednesday for Part Two of this series on Josephine Baker as we celebrate Women’s History Month.